“To the Native people of Southeast Alaska, yellow cedar is more than just a tree. It’s deeply rooted in their culture and mythology. They use yellow cedar to fashion canoes and weave the bark into baskets, carve totem poles and make masks. But it is no myth that for the last hundred years, something has been killing vast stands of yellow cedar.”

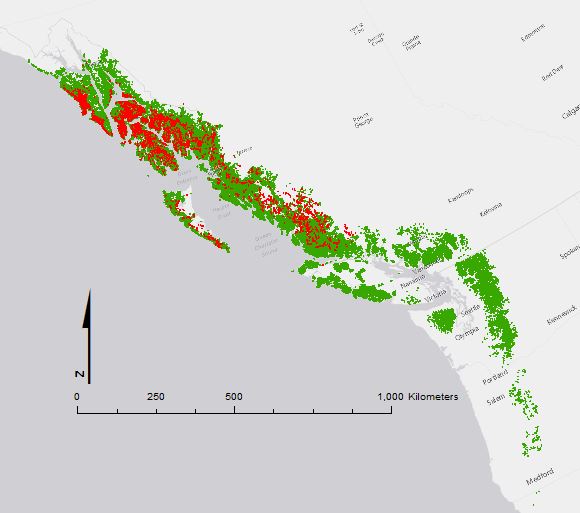

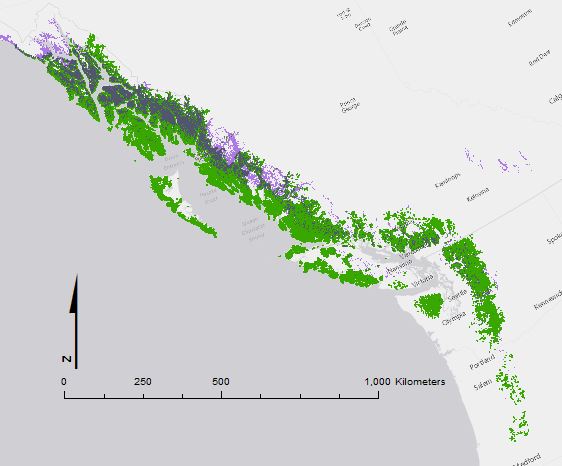

Yellow cedar mortality and signs of expansion. (a): Mortality due to "yellow cedar decline," near Sitka, AK. (b) Signs of expansion: A healthy cedar north of its main range edge near Juneau, Alaska. This tree is ~120 years old. Inset map shows the regional distribution of cedar as well as decline locations, expansion directions, and locations of photos. Photos from USFS and Brian Buma. Reprinted from Krapek and Buma 2015, in Frontiers in Ecology and Environment.

“Based on our review... we find that the petition presents substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that the petitioned action [listing as an Endangered Species] may be warranted for yellow-cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis)”

Range Expansion.

Meanwhile, in the north, yellow cedar appears to be expanding its range slowly. We have found many new founder populations past the main range edge which appear to be young and thriving. Work by John Krapek is determining how fast they are spreading, where they are most successful, and how they are influencing forest understory species. In time, we hope this will influence conservation planning and management.

Yellow cedar: the decline

Over 400,000 hectares of cedar are dying in coastal Alaska and BC. The cause is somewhat counter-intuative - freezing mortality due to a lack of spring snow. We are setting up intensively mapped plots in areas of rapid and recent mortality to look at how forest composition and chemistry changes as the cedar die and are replaced by competing species: Hemlock, spruce, or redcedar (Thuja plicata). The redcedar story is very interesting, as it is a very analogous species in terms of niche and strategies, but not recently related. So will it change the nature of the site? We are doing experimental manipulations as part of a long-term successional study in areas where compound disturbances are hurting yellow cedar populations (decline, harvest).

Cedar decline in climate induced, certainly. So where will it go from here? Ongoing work by the USFS and our lab (undergraduate & graduates are involved) has finally created the first high resolution range-wide map of cedar occurrence (240m), cedar decline (30m), and the projected area of mortality in the future. This phenomena spans 20 degrees of latitude across the old growth forests of the Pacific coast, with decline covering about 9 degrees. This isn't necessarily limited to the coast, either - these forests are the first to lose their persistent winter snowpack, and therefore this may merely be the "canary in the forest" for other currently-snow dominated winter regimes.

The Endangered Species listing would have significant impacts on the local environment. As for the economy, it would likely improve tourism but decrease the income of local loggers and potentially native arts. Yellow cedar is the most economically and culturally important species in the region - like Western redcedar (Thuja plicata), yellow cedar is known for its carvability and resistance to decay. We are working with the regional native corporation, Sealaska, local mill owners (Kuprenoff Lumber, POW mills), and regional economists to investigate how harvesting dead cedar instead of live cedar might provide a useful bridge for local communities. This work, centered in Kake and on Prince of Wales Island, is tracking both the ecological and economic effects of this switch.

Photos courtesy of NSF EPSCoR Alaska, Sarah Bisbing (Cal Poly), John Krapek, and by Brian Buma